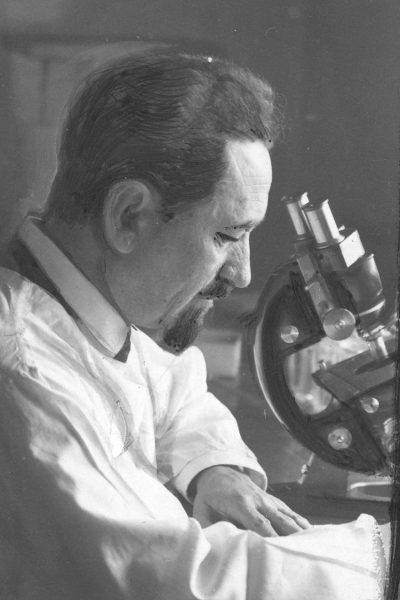

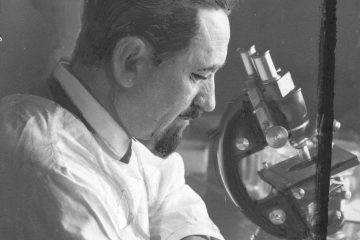

Rudolf Stefan Jan Weigl - world famous biologist

Author: Mariusz Ryńca

Rudolf Stefan Jan Weigl (1883-1957) – biologist, microbiologist, inventor of vaccine against typhus (spotted fever), professor of the Jan Kazimierz University in Lwów, the Jagiellonian University in Kraków and the Poznań University.

He was born on 2 September 1883 in Přerov in Moravia as the son of a Moravian of German origin, Friedrich Weigl, owner of a bicycle and automobile workshop, and Elsa, née Krősl, a Viennese. Rudolf had a sister Lilly and a brother Frederick. After the tragic death of his father, his mother took the children to Vienna, where for some time she ran a dormitory for students. She met and married a Polish man studying there, Józef Trojnar. Since then, the family gradually polonized, especially as they moved to Galicia, where on 30 August 1893 Rudolf’s stepfather accepted a post of assistant teacher of Latin and German at a grammar school in Jarosław. However, they did not stay there long, as Trojnar was hired in 1895 at a secondary school in Jasło, and in 1900 in Stryj.

When the First World War broke out, Rudolf Weigl was appointed to the military medical service of the Austro-Hungarian army as a parasitologist. At the same time, he deepened his knowledge of microbiology studying under Professor Filip Eisenberg. With the support of the Kaiser-King War Ministry, he completed a course in this field and began his research on typhus that was present in the prisoner of war camps in Bohemia and Moravia. In those days the disease claimed millions of victims (on the Serbian front the mortality rate during the epidemic reached 80 per cent).

After Poland regained independence, in the first months of the country’s constitution and battles for its borders, Rudolf Weigl was in charge of a bacteriological laboratory established especially for him in a hospital in Przemyśl, and subsequently, in 1919-1920, of the Typhus Research Laboratory at the Military Sanitary Council of the Ministry of Military Affairs. In 1920, he became full professor of general biology at the Faculty of Medicine of the Jan Kazimierz University, where he taught parasitology and bacteriology. In Lwów, he continued his research into typhus. He also organised a special laboratory for this purpose.

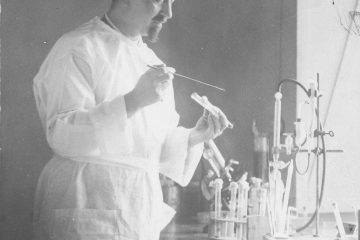

On the basis of his extensive experience as a diagnostician, he developed a method for diagnosing typhus known as the Weigl reaction. He also proved that typhus is caused by a bacterium called rickettsia and identified several species of this bacterium that occur in the bodies of lice. The breakthrough came with the development of a culture method for rickettsia, which required great precision. In laboratory conditions, the microorganism could not multiply, so a live host was needed. For this purpose, Weigl used clothes lice, which he infected by injecting germs into their intestines, where they developed and provided material for vaccines. He fed lice with human blood. He worked as devotedly as ever, as evidenced by the fact that he suffered severe laboratory infections twice (the first time in 1916).

The discoveries enabled Rudolf Weigl to develop a protective vaccine against typhoid fever and introduce it into mass production and use. This was achieved as early as in 1930. A portion of the vaccine obtained from the prepared intestines of thirty clothes lice guaranteed 100% protection after the third dose. The professor was one of the first to test its effect on himself.

The positive results of the research enabled a mass vaccination campaign to be launched in Poland in the early 1930s. The first region to be vaccinated was the Hutsul Region, where typhoid fever outbreaks were common, followed by the Białystok and Suwałki Regions. In 1930, he was awarded the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta by the President of Poland, Ignacy Mościcki. Moreover, due to Weigl’s method, the production of vaccines and vaccination campaigns in other countries were initiated. Pope Pius XI honoured the professor with the title of his chamberlain for saving the health of people working in missions in Asia and Africa, and awarded him with the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Saint Gregory the Great (1934). Weigl was also awarded the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Leopold III by the King of Belgium (1934).

Professor Rudolf Weigl was nominated for the Nobel Prize. He belonged to scientific societies in Poland and abroad (including Belgium and the USA). In 1928, he became a member of the Scientific Society in Lwów, in 1930 of the Polish Academy of Learning, in 1933 of the Scientific Society in Warsaw, and in 1935 an honorary member of the Lublin Scientific Society. In 1937, at the invitation of the League of Nations, he delivered lectures in Geneva at the international conference on eradication of typhus. In 1939, at the invitation of the Italian government, Weigl stayed for several months in Abyssinia, where he worked on developing protective vaccines against various types of typhus in the region. After his return, as a representative of the Health Service Department of the Ministry of Social Welfare, he began to organise the mass production of his vaccine, but the work was interrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War.

Professor Rudolf Weigl was a naturalist by avocation. He liked to spend his holidays with his family in a deserted village Iłemnia in the Carpathian Mountains. There he devoted himself to his hobbies: studying flora and fauna, fishing and archery. He was even a co-founder and president of the Polish Archery Association (1927). He never took part in competitions, despite achieving results comparable to world records.

Rudolf Weigl’s knowledge and experience were used both by the Soviet occupants (after 17 September 1939) and the German occupants (after 22 June 1941). Following the occupation of Lwów by the USSR, the new authorities entrusted him with the post of scientific director of the newly established Sanitary and Bacteriological Institute. Moreover, in Wysock Wyżny, in the Carpathian Mountains, Weigl established a specialist laboratory to fight the outbreaks of typhus, which were frequent in the area. However, in February 1940, when the Institute in Lwów was visited by Nikita Khrushchev, the first secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, the professor did not accept his offer to become an academic at the All-Union Academy of Sciences. The Germans, on the other hand, tried to take advantage of Rudolf Weigl’s German origins and offered him a university chair in Berlin and, in exchange for his inclusion on the German nationality list, promised to support his candidature for the Nobel Prize in 1942. The professor firmly refused. “He was to say then that he had already chosen his homeland and did not intend to leave it at the moment of trial”. He probably took into account the possibility of being sent to a concentration camp, or even of his own death – after all, on 4 July 1941, the Germans shot Polish professors and assistant professors on the Wuleckie Hills in Lwów. Weigl then refused to attend a banquet organised by General Governor Hans Frank, and “his greatest desire became to save as many intellectuals, people of science, culture and students as possible”. Employees of vaccine factories, including lice feeders, were given identification cards and documents that in practice protected them from being arrested in round-ups or during street checks. The remuneration for their work enabled them to support them and their families, while their dwellings were protected by special markings. People in danger of being arrested, sent to forced labour in Germany or killed were employed in production. The factories provided shelter for the Home Army (AK) soldiers, independence activists and people of Jewish origin. It is estimated that the lives of several thousand people were saved in this way, the vast majority of which were representatives of the Polish intellectual elite. Among those who “injected” and fed the lice, inter alia, were: Stefan Banach, Zbigniew Herbert and Eugeniusz Romer.

The Germans opened three large army-run factories in Lwów to produce Weigl’s vaccine – primarily for soldiers on the Eastern Front. The professor personally directed the Institute of Typhus and Virus Research, located on Królowej Jadwigi Street. During the German occupation, the Institute and its branch on Mikołaja Street employed a total of over 5,000 people, while the Behring Institute on Zielona Street employed 1,800. With the approval of Professor Weigl, some vaccines were simply stolen and secretly sent to the ghettos of Lwów, Kraków and Warsaw. As a result of improvements in the production system, around 8 million people were vaccinated on a mass scale. This prevented typhus epidemics in Europe of a scale known from the First World War.

The German army, fleeing from Lwów in July 1944, carried away the equipment of the institutes, and Professor Weigl was forced to leave the city. He settled in Krościenko nad Dunajcem, where he established his laboratory. After the Germans left Kraków in January 1945, he accepted the Chair of General Bacteriology at the Jagiellonian University. He rejected Khrushchev’s proposal to remain in Soviet Ukraine. He started production in Krakow, at the Typhus Research Institute on Sebastiana Street, established by the Ministry of Health in 1947. In 1948-1951, he headed the Department of General Biology at the University of Poznań, where he lectured bacteriology, parasitology and general biology.

The vaccine produced by Rudolf Weigl was the first such effective and widespread protection against typhus. It contributed to the control of the disease in epidemic terms. Other discoveries by the professor contributed to the eradication of the tick-borne Rocky Mountain spotted fever and the Asian disease tsu-tsu-gamushi.

Weigl was unjustly accused of collaboration with the German occupying forces and the Polish communist authorities prevented him from applying for the Nobel Prize in 1946, although in 1953 they awarded him the First-Degree State Prize. The professor died suddenly on 11 August 1957 in Zakopane, during a holiday stay. He was buried on 14 August in Kraków, in the Alley of the Merit at the Rakowicki Cemetery.

Rudolf Weigl was married twice, and both wives were his collaborators. He had an only son, Wiktor, with Zofia née Kulikowska (d. 1940), who was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta in 1931. His second wife since 1943 was Anna, née Herzig.

In 2003, Rudolf Weigl was honoured by the Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem with the title of Righteous Among the Nations. In 2008, a documentary film “To Conquer Death… Prof. Rudolf Weigl” was made (TVP, screenplay and director: Halina Szymura).

The streets named after the professor are located in Kraków, Wrocław (where his monument was also raised). A hospital in Blachownia near Częstochowa was named after Rudolf Weigl.

Bibliography (selection)

Allen A., Fantastyczne laboratorium doktora Weigla. Lwowscy uczeni, tyfus i walka z Niemcami, Wołowiec 2016

Bilek M., Krakowskim szlakiem profesora Rudolfa Weigla, „Alma Mater”, no. 96, 2007, pp. 66–70 (photos)

Biogramy uczonych polskich. Materiały o życiu i działalności członków AU w Krakowie, TNW, PAU i PAN, ed. Andrzej Śródka, part 6: Nauki medyczne, br. 2, Wrocław–Warszawa–Kraków 1991, pp. 299–303 (photos)

Hap W., Poczet wybitnych Jaślan i ludzi związanych z regionem, Jasło 2005, pp. 141–146 (photos)

Łoza S., Czy wiesz, kto to jest?, Warszawa 1938 (photos)

Nagaj B., Dlaczego prof. Weigl nie dostał Nobla?, „Tygodnik Powszechny”, 1992, no. 27

Pawłowski Z.S., Moje wspomnienia o Profesorze Rudolfie Weiglu (1883–1957), „Hygeia Public Health”, 2014, no. 4, pp. 769–773 (photos)

Rudolf Stefan Weigl (1883–1957). Profesor Uniwersytetu Jana Kazimierza we Lwowie, twórca szczepionki przeciw tyfusowi plamistemu, Wrocław 1994

Sprawozdanie dyrekcyi c.k. gimnazyum w Jaśle za rok szkolny 1897, Jasło 1897, pp. V, XXXII

— za r. szkol. 1898, Jasło 1898, pp. 35, 65

— za r. szkol. 1899, Jasło 1899, pp. III, V, XXXVI

— toż za r. szkol. 1901, Jasło 1901, p. 4

Sprawozdanie dyrekcyi c.k. gimnazyum w Stryju za rok szkolny 1902, Stryj 1902, p. 2

— za r. szkol. 1903, Stryj 1903, p. 2

Śródka A., Uczeni polscy XIX i XX stulecia, vol. 4, Warszawa 1998 (photos)

Urbanek M., Profesor Weigl i karmiciele wszy, Warszawa 2018

Weigl-Albert, E. Weigl-Poznańska, Wspomnienie. Prof. Rudolf Weigl, „Gazeta Wyborcza” (Kraków edition), 31.08.2007, p. 11

Wielka encyklopedia PWN, vol. 29, Warszawa 2005

Wójcik R., Kapryśna gwiazda Rudolfa Weigla, Gdańsk 2015

Złotorzycka J., Rudolf Weigl (1883–1957) i jego instytut, „Analecta”, 1998, no. 1, pp. 165–181

Zwyciężyć tyfus – Instytut Rudolfa Weigla we Lwowie. Dokumenty i wspomnienia, ed. Z. Stuchla, Wrocław 2001

Obituaries and post-mortem memoirs: „Dziennik Polski”, 1957 no. 191–192; „Głos Wielkopolski”, 1957, no. 191; „Przekrój”, 1957, no. 649, p. 7 (S. Kryński, photo); „Trybuna Ludu”, 1957, no. 223–224; „Tygodnik Powszechny”, 1957, no. 37; ibidem, 1987, no. 6

Internet (accessed 10.11.2021)

Polacy inspirują – Rudolf Weigl Jagielloński24, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CTy-CLXEno4

Historia bez cenzury, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WggtOfPTiUQ

https://www.geni.com/people/Friedrich-Weigl/6000000099920934953

https://www.geni.com/people/prof-Rudolf-Weigl/6000000099919454975

https://www.geni.com/people/El%C5%BCbieta-Trojnar/6000000099921455861

Map

Miejsce urodzenia

Přerov, Czechy

Miejsce zamieszkania po śmierci ojca

Wiedeń, Austria

Miejsce zamieszkania

Jarosław, Polska

Miejsce zamieszkania

Jasło, Polska

Miejsce zamieszkania

Stryj, Obwód lwowski, Ukraina

Miejsce prowadzenia badań nad tyfusem w obozach jenieckich podczas I wojny

Czechy

Miejsce pracy i badań nad tyfusem plamistym w latach 1918-1920

Przemyśl, Polska

Miejsce uzyskania profesury na Uniwersytecie Lwowskim od 1920 roku, miejsce kierowania Instytutem Tyfusu Plamistego i Badań nad Wirusami

Lwów, Obwód lwowski, Ukraina

Miejsce wygłaszania wykładów nt. zwalczania tyfusu plamistego, 1937

Genewa, Szwajcaria

Miejsce opracowywania szczepionek ochronnych na występujący tam tyfus plamisty, 1939

Etiopia

Miejsce spędzania wakacji

Iłemnia, Obwód iwanofrankowski, Ukraina

Miejsce założenia specjalistycznego laboratorium

Wysocko Wyżne, Obwód lwowski, Ukraina

Miejsce pobytu po opuszczeniu Lwowa

Krościenko nad Dunajcem, Polska

Miejsca objęcia profesury na Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim, miejsce pochówku

Kraków, Polska

Miejsce objęcia profesury na Uniwersytecie Poznańskim

Poznań, Polska

Miejsce śmierci

Zakopane, Polska