Stefan Drzewiecki - pioneer of submarine navigation and aviation

Author: dr hab. Andrzej Olejko, university professor

Mechanical engineer, graduate of the Paris École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, Polish scientist, constructor and inventor, pioneer and aviation theorist, working and creating in France and Russia at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, during the pioneering period of aviation and the crucial period of the development of the world navies. Known all over the world, especially in Russia, not very popular in his homeland.

He was born on 26 July (or December) 1844 in Kunka in Podole, on the territory of tsarist Russia, and spent his childhood years in Jaśkowice in the Latyczów county, in a family of patriotic traditions. By the decision of his parents, he was sent to the research facility of Father Levéque in Auteuil in Paris, where he was to live at 67 rue Boileau with breaks until the end of his life. After passing his matriculation exam, he began studying engineering at the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures, in the early 1860s. During his short stay in his homeland, he joined the January Uprising, however, after the uprising failed, he returned to Paris, where he completed his studies with honours as a promising engineer.

In 1867, Drzewiecki made his first invention, a kilometre counter for horse-drawn carriages, and from that moment the number of innovations developed by him began to increase rapidly. After the fall of the Paris Commune in 1871, he left Paris for Vienna, where he settled at 2 Lindengasse and entirely focused on inventing.

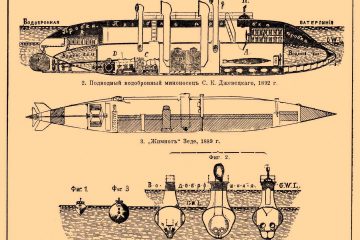

He is remembered in the history of world technology as a pioneer of submarine navigation (designer of submarines) and flight mechanics as well as the inventor of the modern propeller theory. He was the author of numerous patents, both in Europe and in the United States. In 1873, he presented his first inventions at the General Exhibition in Vienna, for which he received two awards. He thereby attracted the attention of Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich Romanov, who invited Drzewiecki to tsarist Russia and appointed him a member and advisor of the Naval Technical Committee. The constructor accepted the offer of employment in St. Petersburg and went to the Romanov Empire, where he worked in 1873-1891. In 1877, he constructed (although not as the first in the world) the original one-man submarine, and in 1879 its four-man version, which was equipped with a periscope and propelled, as the previous one, by the power of the crew’s muscles (this vessel is now exhibited in the main hall of the St. Petersburg Naval Museum). In 1880, he designed a submarine with electric drive, and in 1897 he designed a twelve-person submarine that was also powered by electric engine, for which he received the second prize in the international competition in Paris. Both in the shipyards of tsarist Russia and in the French shipyards fifty submarines were built for the Russian Navy until 1883, in the four-person version based on Stefan Drzewiecki’s patent.

The inventor’s decision to return to France in 1891 did not mean a break in cooperation with Russia. In 1902, Drzewiecki designed the submarine “Pocztowyj”, which was powered by two combustion engines that operated both underwater and after surfacing. However, in his work for the Russian navy, he did not only focus on submarine constructions – he developed a device to launch the so-called Whitehead torpedoes from navy vessels. In France he also developed an original design of a torpedo boat, and in 1897 he designed a submarine for which he won the first prize in a competition announced by the French Ministry of the Navy (the plans of this vessel can be admired in the collection of the Podkarpackie Museum in Krosno, as a gift from the Association of the Polish Army Museum in France). Drzewiecki was honoured by the British Admiralty with the title of the Naval Architect of Great Britain for inventing a device protecting warships from torpedoes. By the end of the First World War, his torpedo launchers were installed on numerous ships belonging to the participating countries.

The second field of the inventor’s interest was aviation. Since 1876, Stefan Drzewiecki was a member of the Imperial All-Russian Technical Society (IRTO). Working in St. Petersburg, he visited the French Republic in the summer of 1882 with the intention of transferring the Société Française de Navigation Aérienne’s experience and scientific research programmes in aeronautics and avionics to Russia. Numerous balloon flights, during which Drzewiecki conducted meteorological research, resulted in a project to improve the flight of free balloons. The “renaissance mind” of the inventor was seriously attracted by the experiments that he observed in the field of emerging experimental aerodynamics, which he considered a prelude to the development of aviation. On 15 November 1882, Stefan Drzewiecki was appointed scientific director of IRTO’s 7th Air Navigation Division and, with a two-year break, remained in office until 1890, simultaneously sitting in the IRTO Council. Since 1881, he was carrying out experiments with planes that glide through the air in St. Petersburg, in 1882 he also organised and conducted observations of the Sun during an eclipse with the use of the balloon L’Astrolabe, since 1883 he worked on the problems of reflex airframe, and in 1885 he conducted experiments with a model of a glider. In April of the same year, during the meeting of the 7th Division, Drzewiecki presented his theory of bird flight and the concept of airframe based on it, as a flying apparatus powered by steam engine with up to 20 HP and 75 m2 of lifting area, capable of reaching the speed of 70 km/h. Drzewiecki’s concept was based on his observations and it was developed over a dozen years before the first flight of Wright Brothers’ airframe in 1903. Its author was the first to prove that the flight of a heavier-than-air device is possible. Drzewiecki’s article L’aviation de demain (Aviation of tomorrow), published in 1891, indicated the scientific direction of research on the theory of flight and the construction of airships, helicopters, ornithopters and gliders. The result of his work, despite a wave of criticism from Polish and other opponents, was the obtaining of a patent in France in 1909 for a reflex aeroplane with the so-called duck (canard) layout. In 1909-1911, Drzewiecki designed a reflex aeroplane (tandem-monoplan, tandem-canard), which was built and later exhibited at the 4th Air Salon in Paris (nowadays the International Air Salon in Paris) in 1912. His works published in 1892 in Russian and French scientific literature – in the field of the theory of gliding flight as well as those concerning the development of the theory of ship propeller and aircraft propeller – were also of fundamental significance. Drzewiecki also was involved in the issues of high-speed turbines, was interested in the kinetic theory of gases, and was one of the pioneers and proponents of the construction of aerodynamic laboratories (for instance the Aerodynamic Institute in Saint Cyr near Paris). In 1909, he became a member of the Commission d’Aviation of the Aeroclub of France, which was founded in 1898. In the same year, the Galician Związek Awiatyczny Studentów Politechniki Lwowskiej (the Aviation Union of Students of the Lwów Technical University) awarded Drzewiecki with the title of its honorary member.

Stefan Drzewiecki widely popularised his theory of the ship propeller, which in 1909 was developed into the theory of the airplane propeller and presented it, inter alia, at the International Congress of Ship Constructors in France. During the First World War, in December 1915, he consented to the free use of his invention patent by the Russian aviation industry. In 1917-1919, approximately 150 propeller models were built in the United States based on Drzewiecki’s theory and tested in aerodynamic laboratories. The results were published in graphic form (also in Russia, in 1932) and were used worldwide to design aircraft propellers. Moreover, during the First World War, Drzewiecki developed field reflectors for the French army, which were tested by the Russian army.

In 1909-1913, he worked on the self-balancing of the airframe, and in 1909-1911 he made a model of a two-seater experimental aircraft with the aforementioned duck (canard) layout, with the lifting planes arranged in tandem, at a scale of 1:10. He experimented with it in the Gustave Eiffel’s aerodynamic tunnel, in Paris. In 1912, Drzewiecki’s reflex plane was built by Ratmanoff company from Paris. The prototype was presented at the 4th International Air Show in Paris, where it was a sensation, followed by flight tests in Chartres in spring 1913. The aircraft was equipped with a water-cooled Labor in-line pushing engine, had four cylinders, a nominal power of 70 HP and a starting power of 80 HP at 1350 rpm. It was equipped with a two-bladed propeller of the “Normale” type designed by Drzewiecki. However, the pilots were reluctant to fly it because of its heavier than expected weight, its unconventional control system and the problems with the engine.

In 1913, the French organisation Chambre Syndicale des Industries Aéronautoques appointed Stefan Drzewiecki its honorary member for his contribution to aviation. He also remained vice-president of the French Aeroclub for a number of years. It was a special honour, as it concerned the only foreigner. In autumn 1913, Drzewiecki proposed an improved version of the canard, powered by a Gnôme Monosoupape engine with 80 HP. Following the tests of the model in an aerodynamic tunnel, the construction of the aircraft began in the spring of 1914. However, the death of its pilot, Major Julien Félix, during the flight (18 June 1914) as well as the outbreak of the First World War interrupted the development of the next version. Drzewiecki’s work on the aeroplane attracted interest of the aviation press in Europe and the United States at that time – it proved that aviation technology had found support in science, which was a novelty then.

On 21 May 1917, Drzewiecki together with a French joint stock company Anciens Établissements Sautter-Harlé applied for a patent of a variable pitch propeller blade (this concept was also patented in Great Britain). His research in the field of propeller theory, which had been carried out since 1892, was published in scientific treatises in 1909 and 1920. In 1919, he patented a metal airplane propeller mounted on a hub in such a way that the angle of the blades could be changed and adjusted before a flight. In 1920, the French Academy of Sciences recognised his work by awarding him a prize.

Drzewiecki also supported Polish aeronautics. For his merits in research and in the field of aviation development, on 25 May 1928 the General Assembly of the National Air Defence League (LOPP) awarded the title of Honorary Member of LOPP to Marshal Józef Piłsudski, to the President of Poland Ignacy Mościcki and to… engineer Stefan Drzewiecki (who later financially supported the construction of the Aerodynamic Institute in Warsaw).

In 1926-1929, Drzewiecki began to work in France on the construction of the adjustable aircraft propeller of his own invention, however, due to many difficulties, France lost priority in this field in favour of other countries, primarily the USA. Nevertheless, the inventor patented a self-adjusting propeller in 1934. The so-called Drzewiecki’s fans, patented by him in 1922, were also widely used in aviation (they were licensed by the French Ministry of Aviation and installed on military aircraft, including those built under French licence by Polish aviation industry in Biała Podlaska and Lublin). In 1926, a prototype turbine invented by Stefan Drzewiecki was built in Switzerland, and in 1930 he became interested in atomic energy.

Since 1891, Stefan Drzewiecki lived in Paris, in a villa opposite which Gustave Eiffel’s aerodynamic laboratory was built in 1909, in the Auteuil district. In his last will, he donated his Parisian studio and library as well as all his works to the Polish State. He died in Paris on 23 April 1938. His words: “The idea of aviation has penetrated today and moved the masses; people have felt that it is through aviation that borders will be abolished and nations will approach each other in universal brotherhood”, remain relevant until this day.

In commemoration of the ingenious Polish constructor, streets in Warsaw, Wrocław, Gdańsk-Zaspa, Poznań, Biała Podlaska and Mielec were named after him. In Szczecin, on Chmielewskiego Street, the centenary of Poland’s regaining independence and the seventieth anniversary of the Gas Company was commemorated by its local branch with a series of murals on the fence of the company. Stefan Drzewiecki is commemorated on one of them. In 2019, Drzewiecki’s merits were also commemorated as part of the Warsaw project “Polish pilots on murals – street art popularising patrons of Okęcie streets”. In 2020, the publication Polacy światu. Znani i nieznani (Poles to the World. Known and unknown) was published by the Department of Cooperation with the Polish Diaspora and Poles Abroad of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Stefan Drzewiecki was also presented among other eight brilliant Poles at the exhibition “Z naszej ziemi, to znaczy Polski – In nostra terra, scilicet Polonia” (“From our land, that is Poland – In nostra terra, scilicet Polonia”).

However, the monument in honour of Stefan Drzewiecki stands in Odessa, not in the Republic of Poland…

List of sources:

Brodzki Z., Stefan Drzewiecki – twórca obliczeń śmigła, „Skrzydlata Polska” 1978, no. 43.

Glass A., Polskie konstrukcje lotnicze 1893–1939, Warszawa 1977.

Glass A., Polskie konstrukcje lotnicze do 1939, vol. 1, Sandomierz 2004.

Kowalski T.J., Malinowski T., Mała encyklopedia lotników polskich, Warszawa 1983.

Januszewski S., Tajne wynalazki lotnicze Polaków. Rosja 1870–1917, Wrocław 1998.

Januszewski S., Wynalazki lotnicze Polaków 1836–1918, Wrocław 2013.

Januszewski S., Pionierzy. Polscy pionierzy lotnictwa 1647–1918, vol. 1, Wrocław 2017.

Jungowski E., Z dziejów techniki, Warszawa 1967.

Liebfeld. A., Polacy na szlakach techniki, ed. A. Liebfeld, Warszawa 1985.

Słownik polskich pionierów techniki, ed. B. Orłowski, Katowice 1986.

Auxiliary sources (accessed 30.12.2021):

https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stefan_Drzewiecki

http://www.samolotypolskie.pl/samoloty/884/126/Drzewiecki-Stefan

Map

Miejsce urodzenia

Kunka, Obwód winnicki, Ukraina

Miejsce lat dziecinnych

Jaśkowce, Obwód winnicki, Ukraina

Miejsce edukacji i studiów, zamieszkania od 1891 i opracowywania wynalazków, miejsce śmierci

Paryż, Francja

Miejsce zamieszkania 1871-1873 i pokazów na wystawie powszechnej swoich pierwszych wynalazków

Wiedeń, Austria

Miejsce pracy 1873-1891 i tworzenia wynalazków

Sankt Petersburg, Rosja

Miejsce wsparcia finansowego budowy Instytutu Aerodynamicznego

Warszawa, Polska