Paweł Edmund Strzelecki - the first Pole who travelled around the world for scientific purposes

Author: Mateusz Będkowski

He is considered to be one of the most eminent Polish travellers and the first Pole who is known to have travelled around the world on his own initiative for scientific purposes. In 1834-1843, he travelled, inter alia, through both Americas, Oceania and Australia, carrying out geological research at the commission of the local authorities. He was also famous for his charity work.

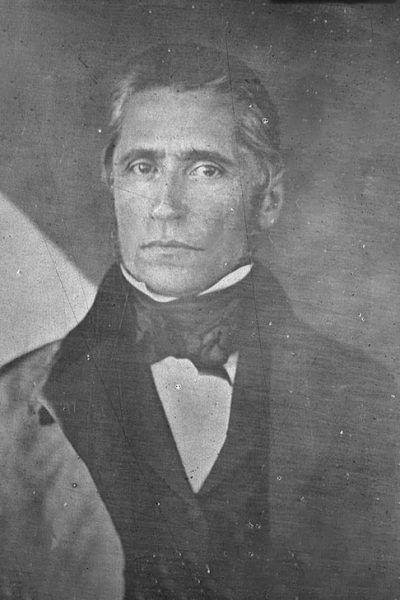

He was born in 1797 in Głuszyna (now within the city boundaries of Poznań), in the Prussian partition, in the family of Franciszek, an insurgent of the Kościuszko Uprising, and Anna, née Raczyńska. He spent his childhood in Wielkopolska, Warsaw and Kraków. After the death of his parents, he was looked after by distant relatives.

Strzelecki was employed for some time as a teacher of the children of the wealthy gentry. In 1819, he met the love of his life, Aleksandra Turno, called Adyna. He wanted to marry her, but the maiden’s father opposed the candidate without any assets. Although the young couple parted in 1822 (though they may have met several times later), Strzelecki loved Adyna for many years and wrote letters to her for a long time.

First travels

Having received money from his siblings – probably from their parents’ inheritance – Strzelecki began travelling around Western Europe. In Italy, he met Franciszek Sapieha, who, impressed by the young Pole’s personality, appointed him the administrator of the Bychowiec estate near Mohylew. Strzelecki administered it for four years, until Sapieha’s death in 1829. The money he saved during that period, as well as part of the money bequeathed to him by the magnate in his last will, was used for further travels and education.

At the end of 1829, he again travelled to Western Europe, probably leaving the Polish territory forever. Since 1831, he lived in England, where he completed a two-year course in geology. In June 1834, in Liverpool, he boarded a ship, thus beginning his voyage around the world. The following month he arrived in New York.

Across the Americas

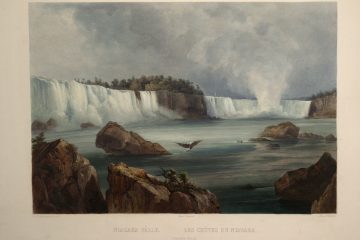

During his first stay in the United States, Strzelecki carried out, inter alia, geological and mineralogical research in the Appalachian Mountain ranges and agrochemical research on farms in Virginia, Maryland and New York State. He also stayed at the Niagara Falls, from where he travelled to the British colonies: Upper and Lower Canada, for several months. In the territory of the first colony, near the Lake Ontario, he discovered copper deposits in 1835, which began to be exploited ten years later.

Then he travelled to Cuba via New York. It is known that he subsequently stayed in Mexico, from where he returned to the United States, where this time the subject of his research were farms in Illinois and Ohio, as well as the desert at the Great Salt Lake in Utah. At the turn of 1835 and 1836, he headed for South America.

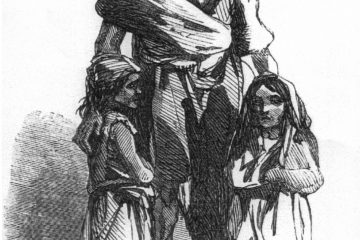

In January 1836, Strzelecki arrived in Rio de Janeiro, where in the harbour he had an opportunity to see a ship stopped by the British with slaves being transported in horrific conditions. The event shocked the Pole, who included his thoughts on the transatlantic human trafficking in his diary, which did not preserve, and then in a book published after his return to England. He spent a total of six months in Brazil, carrying out, inter alia, meteorological, geological, ethnographic as well as archaeological research. He travelled around 5,000 kilometres on the Rio Grande, Parana and La Plata rivers, being impressed by the beauty of the surrounding nature. In August 1836, he arrived in Buenos Aires from Brazil via Uruguay. There he witnessed the execution of a hundred and ten Indian chiefs lured into a trap by the dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas. He also noted this event both in his diary and in a subsequent publication.

At the end of 1836, Strzelecki arrived in Chile, where he continued his research in mining, agricultural chemistry, ethnography and meteorology. In September 1837, he set sail from Valparaiso on the ship Cleopatra, invited by Captain George Grey. The route of the voyage followed the western coast of Latin America: Peru, Ecuador, Costa Rica, El Salvador and Mexico. In the latter, the Pole had enough time to make scientific observations among the Yaqui Indians. He also explored the deposits of raw materials in the states of Lower California and Sonora.

The mystery of Australia

A month after his return to Valparaiso, in July 1838, Strzelecki finally left America. He sailed west and through the Marquesas Islands, Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii; there he was one of the first to make a scientific description of the Kilauea volcano) and Tahiti, he reached New Zealand. During his three-month stay in this British colony, he carried out the first geological survey in the history of the North Island. Afterwards, he went to Australia, which was the most important stage in his journey around the world.

In April 1839, Strzelecki arrived in Sydney, the capital of the colony (now the state) of New South Wales. He spent three months in the city and got acquainted with the local elite, such as the governor George Gipps, on whose commission he explored the continent.

On his first expedition inland, in October 1839, he found gold near Bathurst. The governor ordered him to keep the information secret, for fear of a riot – as the inhabitants of the colony were then largely convicts. However, contrary to some literature, Strzelecki was not the discoverer of the ore in Australia – the first source-confirmed person to come across gold, also near Bathurst, was James McBrien, a government surveyor, in 1823. He was instructed to conceal the fact as well. The New South Wales authorities succeeded in delaying the gold rush until 1851, which lasted in Australia for several decades since its beginning.

During his second expedition, on 15 February 1840, Strzelecki reached the highest peak in continental Australia (2228 metres above sea level) and named it Mount Kościuszko. “The peculiar appearance of this peak struck me so strongly by its resemblance to the mound in Kraków, raised on the grave of the national hero Kościuszko, that although being in a foreign country, on a foreign soil, but among people who valued freedom and its defenders, I could not refrain from naming the mountain Mount Kościuszko” [1]. In English-speaking countries, the easier-to-pronounce name Mount Kosciusko was adopted, although, in 1997, the New South Wales Geographical Names Commission changed it to one closer to the original: Mount Kosciuszko. Noteworthy is the fact that the fertile land which Strzelecki explored at a later stage of this expedition, he named after the aforementioned governor as Gippsland (currently the eastern part of the state of Victoria). The term is used until today.

Return to Europe

From July 1840 to September 1842, the Polish traveller stayed mainly in van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania). There he discovered and described deposits of coal, copper and gold-bearing quartz. Then he went via Sydney to Port Stephens near Newcastle, from where he set off on his third Australian expedition, this time north. He then studied the geology of the Hunter and Karuah river valleys. In April 1843, he returned to Sydney, from where, because of his deteriorating health, he sailed for Europe. He made his journey to Suez among other places via Timor, Bali, Canton and Singapore. Having then visited Malta, Algiers and France, he arrived in London, completing his voyage around the world in October 1843.

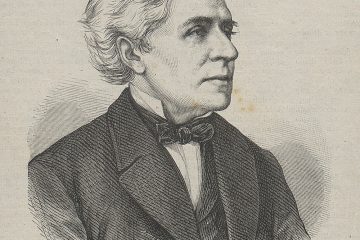

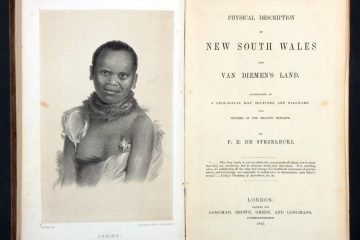

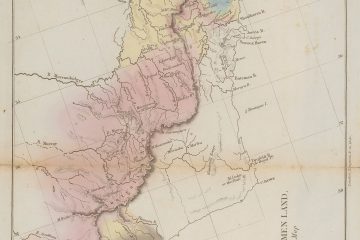

After his return Strzelecki settled in England. In 1845, he accepted British citizenship and published the aforesaid book containing, inter alia, the results of his Australian and Tasmanian research, entitled Physical Description of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (in Polish it was published as Nowa Południowa Walia, in 1958), as well as the first so detailed geological map of those areas. His work brought Strzelecki recognition in the scientific community, including that of Charles Darwin himself. In 1846, he was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society.

Later activities

Between 1847 and 1849, as an agent of the British Relief Society, Strzelecki was involved in organising and supervising aid for the victims of the Irish famine caused by the potato blight. He received the Order of the Bath from the British government for his work in November 1848. Noteworthy is that he did not accept remuneration for his work. Unfortunately, he fell ill with typhoid fever in Ireland, the effects of which he would suffer for the rest of his life.

In 1853, he became a member of the Royal Society in London as well as the first Pole of the Royal Geographical Society. Just after the Crimean War, in 1856, he participated as an envoy of the British in a secret mission to the Crimea, at least for several months. The role he then played is unknown.

In 1857, Strzelecki was raising funds for one of the expeditions aimed at finding the lost ships Erebus and Terror, which had sailed from England over a dozen years earlier under the command of John Franklin. The Pole had met him personally on van Diemen’s Land, when the latter held the office of governor there. Franklin’s expedition was to find and explore the Northwest Passage between the Baffin Sea and the Bering Sea. However, both ships were ice-bound before reaching their destinations. The crews did not survive, and none of the dozens of rescue expeditions found the wrecks. This was only achieved by Canadian scientists, due to melting glaciers, in 2014 (Erebus) and 2016 (Terror) respectively.

In 1860, Strzelecki received an honorary doctorate in civil law from Oxford University, and nine years later the Order of St Michael and St George as well as a knighthood Sir from the Queen Victoria.

Commemoration

Strzelecki died on 6 October 1873 in his London house, of liver cancer. As far as is known, he never got married and had no children. He was initially laid to rest in the Anglican cemetery of Kensal Green, in a marked grave (against his will; he wished to be buried anonymously, without any religious symbols). In 1940, during the bombing of London by the Germans, the gravestone was damaged. Three years later a new, larger one was erected. In 1997, the traveller’s remains were exhumed and transported to Poznań, where they were placed in the crypt of the distinguished on Wzgórze Świętego Wojciecha (the St Wojciech Hill).

Strzelecki has been commemorated in numerous ways. In his honour, inter alia, the Strzelecki Mountains in South-East Australia were named after him, a low mountain range whose highest peak is 740 metres above see level). Furthermore, an eleven-metre-high monument was erected to him near Mount Kosciuszko in Jindabyne, New South Wales. The monument was created at the initiative of the Polish-Australian Cultural Association in Sydney. It was made entirely in Poland by Jerzy Sobociński and unveiled in 1988. On Mount Kosciuszko there is a plaque informing that it was conquered and named by that Polish traveller. Two much smaller monuments in honour of the geologist are also located in Poznań. Whereas in 2015, a plaque was placed in Dublin to commemorate the humanitarian aid given to the Irish during the Great Famine. It was founded by the citizens of Poznań with the support of the Irish-Polish Society, the Irish Culture Foundation as well as the Dublin City Council.

List of sources:

Strzelecki P.E., Nowa Południowa Walia, PWN, Warszawa 1958.

Strzelecki P.E., Pisma Wybrane, ed. W. Słabczyński, PWN, Warszawa 1960.

Studies:

Będkowski M., Polacy na krańcach świata: XIX wiek, Promohistoria–Wydawnictwo CM, Warszawa 2018.

Molski F., The Best of Human Nature. Strzelecki’s Humanitarian Work in Ireland, Kosciuszko Heritage, Sydney 2012.

Official website of the association Mt Kosciuszko Incorporated, http://www.mtkosciuszko.org.au, [accessed: 8.11.2021].

Paszkowski L., Sir Paul Edmund de Strzelecki: Reflection on His Life, Arcadia: Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne 1997.

Paszkowski L., Strzelecki Paweł Edmund, [in:] Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. 44, Wydawnictwo PAN, Warszawa–Kraków 2006–2007, pp. 631–637.

Słabczyński W., Paweł Edmund Strzelecki. Podróże – odkrycia – prace, PWN, Warszawa 1957.

Słabczyński W., Polscy podróżnicy i odkrywcy, PWN, Warszawa 1988.

[1] Paweł Edmund Strzelecki, Raport o odkryciu Ziemi Gippsa. Sprawozdanie hr. Strzeleckiego, [in:] Pisma wybrane, p. 33.

Map

Miejsce urodzenia

Głuszyna, Poznań, Polska

Pierwsza z podróży, spotkanie z Franciszkiem Sapiehą

Włochy

Miejsce pracy jako zarządca majątku Bychowiec

Mohylew, Białoruś

Miejsce ukończenia studiów geologicznych i zamieszkania po podróży dookoła świata

Anglia, Wielka Brytania

Początek podróży dookoła świata, 1834

Liverpool, Wielka Brytania

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata i prowadzony badań

Nowy Jork, Stany Zjednoczone

Miejsce przeprowadzanych badań

Appalachian Mountains

Miejsce przeprowadzanych badań

Virginia, Stany Zjednoczone

Miejsce przeprowadzanych badań

Maryland, Stany Zjednoczone

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Niagara, Niagara Falls, Nowy Jork, Stany Zjednoczone

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata i prowadzonych badań

Ontario, Kanada

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata i prowadzonych badań

Quebec, Kanada

Miejsce odkrycia w 1835 roku pokładów miedzi

Ontario (jezioro)

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Kuba

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata i prowadzonych badań

Meksyk

Miejsce przeprowadzanych badań

Illinois, Stany Zjednoczone

Miejsce przeprowadzanych badań

Ohio, Stany Zjednoczone

Miejsce przeprowadzanych badań

Great Salt Lake Desert, Utah, Stany Zjednoczone

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata, 1836

Rio de Janeiro

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata i prowadzonych badań

Brazylia

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata, 1836

Buenos Aires, Argentyna

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata i prowadzonych badań

Chile

Początek rejsu wzdłuż zachodniego wybrzeża Ameryki Łacińskiej oraz rejsu do Nowej Zelandii

Valparaíso, Chile

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Markizy, Polinezja Francuska

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata i prowadznych badań

Hawaje, Stany Zjednoczone

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Tahiti

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata i prowadzonych badań

Nowa Zelandia

Miejsce przybycia do Australii i początek badań kontynentu, miejsce podróży powrotnej do Europy

Sydney Nowa Południowa Walia, Australia

Miejsca odkrycia złóż złota, 1839

Bathurst Nowa Południowa Walia, Australia

Zdobycie szczytu 15.02.1840 i nadanie nazwy Mount Kościuszko

Góra Kościuszki, Kosciuszko National Park Nowa Południowa Walia, Australia

Miejsce badań i odkryć w okresie 1840-1842

Tasmania, Australia

Początek III wyprawy w głąb Australii

Newcastle Nowa Południowa Walia, Australia

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Timor

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Bali, Indonezja

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Kanton, Guangdong, Chiny

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Singapur

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Suez, Egipt

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Malta

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Algieria

Na trasie podróży dookoła świata

Francja

Miejsce zakończenia podróży dookoła świata, miejsce śmierci

Londyn, Wielka Brytania

Miejsce organizowania pomocy dla ofiar zarazy ziemniaczanej w latach 1847-1849

Irlandia

Miejsce tajnej misji z ramienia rządu bryrtyjskiego, 1856

Krym

Miejsce pochówku w 1997 roku

Wzgórze Świętego Wojciecha, Poznań, Polska

Miejsce zamieszkania w okresie dzieciństwa

Warszawa, Polska

Miejsce zamieszkania w okresie dzieciństwa

Kraków, Polska