Maria Zakrzewska - pioneer of women’s health care

Author: prof. dr hab. Anita Magowska

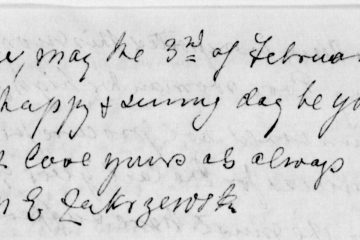

“I am very proud of my aristocratic origin, but I would like to be remembered only for what I do for the enhancement of women”, wrote Maria Elżbieta Zakrzewska in a letter to one of her friends. This enterprising, energetic and aware of her dignity Polish woman was one of the most remarkable women of the 19th century as well as one of the most outstanding reformers of American medicine.

Her father, Ludwik Marcin Zakrzewski, was descended from the borderland gentry, whose lineage reached back to the Middle Ages and whose vast landed estates were seized by the Russians after the Second Partition of Poland. Her mother, Caroline Fredericka Wilhelmina, née Urban, was the great-granddaughter of the pretty queen of the Gypsies of Lombardy. Maria was born on 6 October 1829 in Berlin as the eldest of their six children. Her father worked as a clerk, but when his liberal views caused him to be sent into premature retirement, the family fell into poverty. In order to improve the family finances, Maria’s mother enrolled in a government school for midwives in Berlin, and subsequently she developed quite substantial practice.

Having finished primary school, thirteen-year-old Maria began to assist her mother with home visits. She decided to become a midwife influenced by the experience of taking care of a terminally ill relative, when, as she recalled, she “learned to smile at the suffering”. Moreover, reading medical books awakened in her a vocation to the medical profession.

In accordance with the customs of the time, an application to the authorities for admission to the school of midwives at the Royal Charité Hospital in Berlin was written by her father on behalf of Maria. However, she was not accepted because she was only eighteen and unmarried. For the next two years her efforts were unsuccessful, until finally Joseph Hermann Schmidt, professor of obstetrics and director of Prussia’s largest Charité Hospital and school for midwives, as well as personal physician to the King of Prussia, interceded on her behalf with Frederick William IV. He remembered Maria from the time when she was helping her mother in the midwifery practice and he held her in high esteem.

He enabled Maria to enrol in the midwifery school, where she performed so well academically that Schmidt appointed her an assistant teacher. And when she passed her final exams, he made efforts to employ her as chief midwife of the Royal Charité Hospital. “A woman is also capable of holding a high position”, explained the already seriously ill doctor to the King of Prussia. He died just a few hours after the king had granted his consent.

On 15 May 1852, young Maria obtained the prestigious post, however, after her patron’s death, she faced widespread reluctance at the hospital. She resigned her post after six months in order to seek her life’s chance in America. In the spring of 1853, she left the family home and arrived in Hamburg with her younger sister Anna, and then they travelled to New York by sea.

When the ship docked, the girls were shocked. They did not understand what was being said to them because they did not speak English. They had no one to help them. No doctor wanted to employ Maria as an assistant. Anna had to work as a dressmaker for less than three dollars per week, which was scarcely enough to live on. However, one day she did not receive a penny for her work because the factory owner had not been paid for his goods. Maria then encouraged her to set up her own business. The sisters cleverly obtained credit and hired female homeworkers to embroider and knit clothes.

The breakthrough in their lives came a few months later when Maria managed to make contact with Elisabeth Blackwell, the first woman to graduate as a doctor in the United States. They were like two kindred spirits and soon a warm friendship developed between them. Both dreamed of a hospital that would only employ and treat women. However, first Maria had to learn English. Elisabeth gave her lessons twice a week, while at the same time writing applications to American medical schools on her friend’s behalf, asking for admission and a loan for her studies. Only the Cleveland school responded positively, promising a long-term loan.

When Mary arrived in Cleveland in October 1854, she again experienced an unpleasant surprise. She found herself among men studying medicine who looked at her with contempt. She also had no one to live with on campus. Moreover, her English was poor and she understood little of the lectures.

During that difficult period, she was contacted by Caroline M. Severance, the president of the all-female Physiological Society. She accommodated Maria in her own home and provided her with material assistance from a special fund that the organisation had established for female medical students.

In 1856, the twenty-seven-year-old Mary, with her medical degree and diploma in hand, returned to New York to search for work, however, she was met with ostracism and reluctance. Her inability to practice medicine prompted her and Elisabeth Blackwell to raise funds to establish their own medical clinic for poor women and children. In May 1857, the clinic was opened as The New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children.

When Maria visited Boston two years later, she was fascinated with the beauty of the city and decided to stay. She accepted a post as professor of obstetrics at Boston’s Women’s Medical School, discovering that she was accepted as a doctor there. She focused her teaching efforts on providing female students with the same clinical practice as male medical students. However, when the founder of the university, Samuel Gregory, announced that he would be awarding female graduates the title of she-doctor instead of doctor, she was outraged and resigned the post.

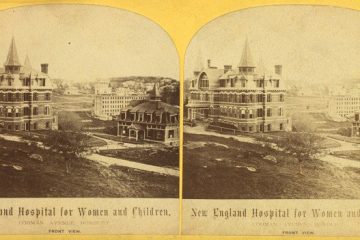

In July 1862, in the southern part of Boston, where a large number of poor people lived, she opened a hospital for them known as the New England Hospital for Women and Children. It was the first institution in Boston and the second in the United States where the doctors and surgeons were exclusively women. It occupied a large site with several buildings surrounded by greenery. According to Maria’s intentions, only women doctors and nurses gained clinical experience in the hospital. However, entire separation of the women’s hospital from the male doctors proved to be impossible, since only they were specialists in such then new fields of medicine as psychiatry and neurology. Thus, they were employed as consultants.

Twenty-five-year-old Susan Dimock, a graduate in medicine from the University of Zurich, who was employed at the hospital in 1872, has passed into history. When she died in a shipwreck after three years of work, it was decided to commemorate her by naming one of the buildings after her.

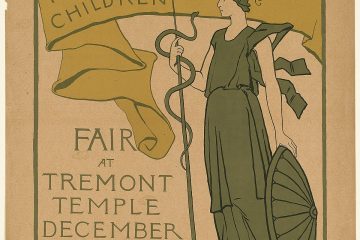

The principle introduced by Zakrzewska was that the medical staff would perform half their work selflessly. Nevertheless, the costs of running the hospital were too high to be covered by the fees paid by its patients (a three-week stay in a dormitory room cost 20 dollars, and in a private room 75-90 dollars). Moreover, a quarter of the patients were released from the obligation to pay for their stay and treatment due to their poverty. Therefore, the hospital management willingly accepted donations of used bedding, unwanted kitchen utensils and already read books (for the library), as well as vegetables and fruit for the patients. Every three years a fair was organised, the profits from which supported the hospital budget.

In the hospital, female surgeons carried out gynaecological operations within the full scope known at the time, including oncological ones, but they also performed surgeries such as amputations. The results of treatment were, for those times, good. Typical of the medical capabilities at the turn of the century, was the death rate among new-borns – around 3.5 per cent.

The development of the Boston hospital might suggest that Maria Zakrzewska succeeded in changing Americans’ attitudes towards women doctors, and even if she did not, she won widespread respect because of her entrepreneurship, nobility and knowledge. However, that was not the case. She never gained recognition from the male doctors’ organisations. She was well known in Boston and Massachusetts, but despite her enormous contribution to medicine and the community, the local medical society refused her membership because of her gender. Moreover, when, acting together with other female pioneers of American medicine, she offered Harvard University the then astronomical sum of $50,000 to establish a medical school for women, her offer was rejected.

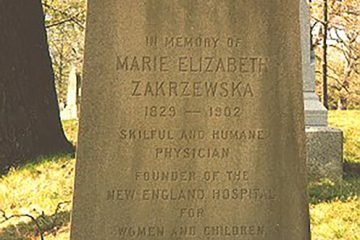

In 1889 Zakrzewska resigned from the management of the hospital, although she continued her lifelong battle for women’s access to the medical profession. She died on 12 May 1902 of a heart attack in her villa in Jamaica Plain, a district adjacent to the hospital. Her death was noted by all American newspapers, emphasising that when Lady Doctor had arrived in the United States almost half a century earlier, female practice as a doctor was not accepted.

Map

Miejsce urodzenia, ukończenia szkoły powszechnej i szkoły położnych, objęcia funkcji naczelnej akuszerki Królewskiego Szpitala Charité

Berlin, Niemcy

Na trasie wyjazdu do Ameryki w 1853 roku

Hamburg, Niemcy

Miejsce przybycia do Ameryki i otwarcia lecznicy dla ubogich kobiet i dzieci

Nowy Jork, Stany Zjednoczone

Miejsce ukończenia studiów medycznych

Cleveland, Ohio, Stany Zjednoczone

Miejsce pracy jako profesor położnictwa w Bostońskiej Żeńskiej Szkole Medycznej, otwarcia New England Hospital for Women and Children

Boston, Massachusetts, Stany Zjednoczone

Miejsce śmierci

Jamaica Plain, Boston, Massachusetts, Stany Zjednoczone